“I’ve got a lovely bunch of coconuts, fiddeldy-dee.” whenever I mention to my dad that he should really give coco coir a go in his greenhouse, this is what he usually ends up singing In return. I’m not sure if it’s an age thing but sometimes convincing the older guys to use anything but peat is bit like trying to convince flat earther’s the moon isn’t really a giant hologram. He is already set in his ways I guess, unlike the new generation. They have embraced coir as an alternative for growing with mucho gusto.

At the very least, coir does look a little bit like peat. So that’s the first hurdle overcome for the older boys to begin considering it as an alternative. Other aspects of growing with coir aren’t quiet as similar though, but not so far removed that it should become a daunting challenge for them. Coir is a fantastic medium to use. All it takes to get the most out of coir is understanding the nuances that make it so great, and ultimately how you can use them to your advantage. That’s essentially the premise of this entire article. We are going to lay bare the principles of coir as a substrate and dig deep into its many forms and applications thereof. Knowledge is power folks. The right sort of knowledge of course. Harking back to the flat Earth example, the right mind set combined with the wrong information can prove to be an entirely different scenario altogether.

Pure Coco

The easiest (and actually the most practical) way in which to make use of coir is completely pure and unadulterated. Like we eluded to earlier, coir has it’s own very unique physical properties both in terms of aeration/water retention and also nutrient holding abilities or Cation Exchange Capacity(CEC). While combining other materials into the mix can sometimes have positive benefits to plant growth, it can also sometimes overly complicate the inner workings of the substrate to the point where it will actually stifle any advancement. To begin to understand exactly why this is, we first need to look at the individual parts of the equation, rather than just focus on the sum.

Forms of Pure Coir

Currently available in any self respecting retailer will be a plethora of different brands of coir. What you need to be able to deduce as a discerning shopper is what the differences are between them and which of them are likely to work best for your particular grow room and irrigation system. There are three main horticultural grades of coir used by the various brands on the market, and each brand will have a slightly different percentage of each in their own particular recipe. They will generally be a combination of:

Pith/Dust

The super fine particles of dust, called pith, remaining from the washing and buffering process. Excellent water holding capabilities and an ideal base for starting seeds. However too much dust will result in compacted and poorly aerated medium.

Coarse

Slightly larger and more strand like, fibrous coir that provides an excellent source of air pockets and offers great drainage capabilities. The natural capillary action of the fibrous strands help provide a more even saturation throughout the pot.

Coarse chips

Larger coarse chips and fibrous strands. Provide an abundance of air pockets, and a fantastic level of drainage. Using exclusively this grade as a medium offers the high end efficiency and usability of a more inert substrate like rockwool, yet it is still classed as an organic substrate.

Bags, Slabs or Blocks?

So once a healthy balance of the three grades of coir has been determined, they are combined and bagged up for sale. Most commonly you will find it loose filled in 50 Litre bags, that should be measured out according to strict EN regulations. Loose fill bags are most certainly the easiest to use but when you have a dozen or more bags to move, transportation problems can rear their ugly head.

Coir in slabs offers the possibility to install a coir based system in exactly the same way as you would with a rock wool slab system. Making use of the chip grade of coir within slabs offers a surprisingly efficient, and natural alternative to rock wool. However, if the more complex irrigation strategies that come with this type of substrate put you off, then the more fibrous grade of slabs offer a happy medium between the two.

Blocks of compressed coir make for a fantastically transportable medium. No huge and heavy bags to carry around, just a nice and light compressed block. In general, the problems that come with compressed blocks is that they are typically made of poorly washed/buffered coir and that you have to spend quite some time ensuring it all expands nice and evenly. However, in more recent times you can find compressed coir that is of exactly the same quality you will find in a premium loose fill bag and you can find brands that have innovative methods for expansion that take all the effort out of it for you. Just be sure to choose a reputable source.

Amending Coir

People always want the next best thing. When the next best thing isn’t on the market yet, people tend to try and create it themselves. While results with using pure coco as a growing medium cannot be easily argued with, there are of course situations in which amending the mix can prove beneficial to a particular grower’s circumstance. Understanding what you are doing to the properties of the mix as a whole is key to achieving these benefits. However you amend your coir it will affect the resultant properties in either one or both of two ways: mechanically or chemically.

Amending to alter mechanical properties

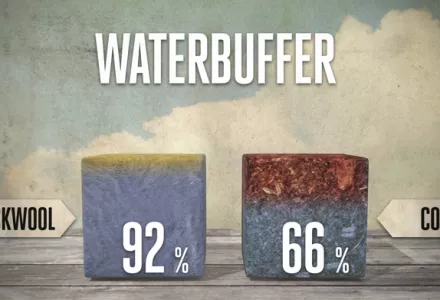

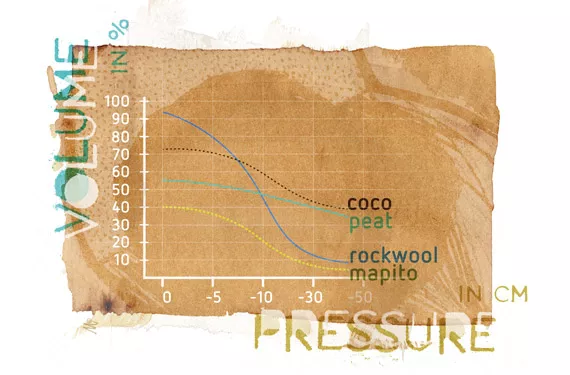

When products like perlite, vermiculite or clay pebbles are added to coir, they are primarily affecting drainage and aeration of the total medium. As well as the natural differences in shape and size that affect this, every substrate has its own capacity to hold on to water. You can see in the graph pictured here, four typical media. Along the Y axis is their volume in water and along the X axis the pressure at different heights in cm. As the height increases so too does pressure and each medium retains a different proportion of its entire water holding capacity. Essentially this shows how well each of them holds on to water, or you can can look at it another way and say it is their willingness to let go of water.

Looking at the blue line for rockwool, you can see it has a higher initial water holding capacity than coco, and the quick curve downwards shows that it lets go of water more easily and to a lower end point than coco. By comparison, looking at the black dotted line for coir, it has a much higher initial water holding capacity than peat and lets go of water at a quicker rate than peat to an almost similar end result. The shallow green line for peat indicates that peat really likes to hold on to water compared to the rest!

So primarily what you will notice when amending with perlite or clay pebbles is the pot drying out at a faster rate and so an increased frequency of irrigation will be necessary. This is because you are reducing the overall water holding capacity of the pot as a whole and also because you are ‘watering down’ the coir and thus reducing its resistance to water loss under increasing pressures. What you would see the line become on the graph is a slightly lower starting point, with a slightly steeper downward trend in the middle, to a slightly lower end result.

It is not just the mechanical properties of coir you will affect with pebble or perlite amendments, particularly with some brands of pebbles. Many residual salts can be left behind which can play havoc with coir’s own natural CEC, and particularly how it has previously been buffered. Make sure to choose only the cleanest of sources when wanting to amend mechanically alone.

Amending to alter nutritional properties

This is generally where it tends to become tricky with coir. As mentioned earlier it’s by no means a direct replacement for a peat substrate and nowhere is that more evident than when it comes to adding chemical or organic fertilisers to it. The main contributing factor is the Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) of coir.

Don’t get scared by the scientific looking words. In a nutshell (excuse the pun) all it really means is the total storage capacity something has for nutrients. What it actually is, is a measure of the amount of negatively charged sites that a potential positively charged cation could adsorb to. So the higher the CEC, the higher the potential storage capacity for nutrients there is.

Although coir does have a relatively high CEC, compared to peat, there is little to boast about. What this means is that if you amend with a chemical fertiliser, its longevity in coir may not be what you are used to with a peat mix. With the lower CEC there is not the capacity to hold all the immediately soluble cations and so a lot more is washed out on each watering relative peat.

Longer term organic amendments may seem like a more tempting route to go down, as with the slower release of nutrients, it will not be washed out of the fibres as quickly as a chemical fertiliser, but do not be so hasty in going down that route. The overall properties of the medium will be altered which will in turn causes further issues.

Organic amendments will have their own unique pH value, sometimes high, sometimes low. Adding these amendments into your coir will either raise or lower the overall pH of your substrate accordingly, often to detrimental levels. This will cause significant swings in pH that would otherwise be negated in a peat mix with its lime buffer.

Secondly, on top of not having the long term storage capabilities of nutrients in the way peat does, you can never be quite sure what exactly is being released by the amendments, and at what rate they are being released. This could very easily have knock on effects to the other type of buffering in coir, calcium. This in turn could have a detrimental effect on the overall availability of elements in the nutrient solution that you (try to) supply to the plant. As an obvious example, it might be getting less calcium and more potassium than it should.

Thirdly, organic amendments very much depend on a healthy and diverse micro life present in your substrate. Some of the more premium coirs on the market will contain Trichoderma, but solely relying on those will not cut the mustard when it comes to an efficient cycling of organic based additives. The result of which will be an insufficient and sporadic release of the nutrients, so you will never quite know where you stand with what is actually in your pot.

Using Coir as an amendment

Another possibility for coir is that it can be utilised as an amendment itself. With all the hullabuloo surrounding the continued availability of peat as a sustainable medium, it’s now more and more common to find peat mixes that contain a high level of coir as a total percentage of the substrate.

It can make a fantastic additive to a peat based mix when used correctly, and it’s different physical properties properly accounted for (Usually no more than 30% before the attributes of the coco affect the way the final mix will work as a whole).

Similarly, coir can be used to great effect to improve and condition poor types of soils in an outdoors environment. A dense clay soil could benefit immensely from the addition of coir. The coir will help prevent compaction and introduces a much greater level of aeration and drainage to the soil as a whole.

Keep It Simple Stupid

Coir is a fantastic substrate on its own right. The ease of use and efficiency it has is almost second to none. If you do choose to amend your coir, you could potentially be walking into a hit-and-miss situation. If you do go down this route, make sure you take it slowly and don’t go straight in and overload it with everything in the cupboards all at once.

More often than not, you will find it is best to leave the cupboards alone altogether. Mother Hubbard will thank you for it as well as your plants.